How to Cite | Publication History | PlumX Article Matrix

In vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Crude Plant Chewing Sticks Extracts on Oral Pathogen

M. N. Abubacker1*, K. Kokila2 and R. Sumathi2

1Department of Biotechnology, National College, Tiruchirappalli - 620 001, India.

2Department of Botany, National College, Tiruchirappalli - 620 001, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: abubacker_nct@yahoo.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/1032

ABSTRACT:

In vitro antimicrobial effects of natural plant chewing stick extracts of Accacia arabica, Azadirachta indica, Ficus bengalensis, Mangifera indica, Pongamia glabra and Salvadora persica on oral pathogens was conducted to prove scientifically about the epidemiological and clinical beneficial effects of chewing sticks on oral hygine. Oral pathogens isolated from the oral cavities of student community were Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. lactis, Proteus vulgaris and Streptococcus mutans which cause gingivitis (inflammation of gums), periodontitis (inflammation of supporting tissues of teeth) and plaque. The antimicrobial effect of chewing stick extract revealed that S. persica, A. arabica and A. indica are highly effective against oral pathogens whereas F. bengalensis, M. indica and P. glabra are less effective when compared with ethanol, methanol and standard antimicrobial disc used as positive control. The different response of each microbe to the various chewing stick extracts indicated that the natural chewing stick posses different phytochemical compounds which inhibited the growth of oral pathogens.

KEYWORDS: Antimicrobial activity;Chewing sticks; Crude extract; Oral pathogens.

| Copy the following to cite this article: Abubacker M. N, Kokila K, Sumathi R. In vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Crude Plant Chewing Sticks Extracts on Oral Pathogen. Biosci Biotech Res Asia 2012;9(2) |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Abubacker M. N, Kokila K, Sumathi R. In vitro Antimicrobial Effects of Crude Plant Chewing Sticks Extracts on Oral Pathogen. Biosci Biotech Res Asia 2012;9(2). Available from: https://www.biotech-asia.org/?p=9926 |

Introduction

Dental decay is a chemical parasitic process consisting of two stages, the decalcification of enamel or its total destruction and the decalcification of dentine (dissolution of the softened residue)3. The carcinogenic Streptococci is critical to the development of pathogenic plaque. A large number of Streptococcus, Actinomyces and Lactobacillus species are involved in root caries and periodontal diseases4. Antibiotic resistance has increased substantially in the recent years and is posing an ever increasing therapeutic problem5, 6. One of the methods to reduce the resistance to antibiotics is by using antibiotic resistance inhibitors from plants7.

Plants are known to produce a variety of compounds to protect themselves against a variety of pathogens. It is expected that plant extracts showing target sites other than those used by antibiotics will be active against drug resistant pathogens8, 9. Medicinal plants have been used as traditional treatment for numerous human diseases for thousands of years and in many parts of the world. In rural areas of the developing countries, they continue to be used as the primary source of medicine10. About 80% of the people in developing countries use traditional medicines for their health care11.

The World Health Organisation has recommended and encouraged the use of chewing sticks. Recently, chewing sticks have been comprehensively reviewed and examined for their effectiveness in oral hygiene12, 13.

There is a long history of the use of plants to improve dental health and promote oral hygiene. In various parts of the world where tooth brushing by modern method is uncommon, the practice of tooth cleaning by chewing sticks is very commonly observed. This practice was recorded by the Babylonians in 5000 BC. This natural tooth brushing is very common today among many African and Southern Asian communities as well as in isolated areas of tropical America and the southern United States. In many African homes teeth are cleaned in the morning by chewing the root or slim stem of certain plants until they acquire brush like ends. The fibrous end is then used to brush the teeth thoroughly14.

The aim of this study was to compare the antimicrobial effects of six different chewing sticks commonly used by Indian population using crude extract against the oral pathogens.

Materials and Methods

The plant chewing stick used for the present work were Acacia arabica Willd (Mimosoideaceae), Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae), Ficus bengalensis Linn. (Moraceae), Mangifera indica Linn. (Anacardiaceae), Pongamia glabra Vent. (Fabaceae), Salvadora persica Linn. (Salvadoraceae) (Fig. 1 and 2).

|

Figure 1

|

|

Figure 2

|

Acacia arabica (Mimosoideaceae)

The babool tree (Karuvelam) known to contain galactoaraban, arabic acid as phytochemical constituents of the chewing stick. A. arabica a moderate sized tree with golden-yellow flowers, long white thorns and characteristic whitish-tomentose pods which are eaten by cattle. Bark dark brown, rough, wood reddish brown, hard and strong used for agricultural purpose.

Azadirachta indica Juss (Meliaceae)

The neem tree, in Sanskrit, Nimba and Arishta, is a native of India, and is cultivated in all parts of the subcontinent on account of its medicinal properties. The leaves, bark and other products of Neem have been articles of the Indian materia medica since antiquity and are mentioned in the Ayurveda of Sushruta. The active principles of the plant were brought to the attention of natural products scientists in 1942, named as nimbin, nimbinin, and nimbidin. Azadirachtin is a chemical compound belonging to the limonoids was later identified. Neem mouth rinse is very effective in the treatment of infections, tooth decay, bleeding and sore gums. A mouthwash, using Neem oil, has been manufactured and used for the treatment of mouth ulcers.

Ficus bengalensis Linn. (Moraceae)

The Banyan, a large tree throwing out numerous large aerial roots from the main trunk and large branches, which descend to the soil and form supports, and capable of separate existence when severed from the parent tree. Bark is grayish-white, wood grayish-white and moderately hard is used for various purposes. The stem stick is used as chewing stick for oral hygine.

Mangifera indica (Anacardiaceae)

The mango tree a large spreading evergreen tree reaching 50 ft in height, the oblong-lanceolate shining leaves crowded at the ends of the branches, the flowers in dense terminal panicles, cultivated for its edible and very important fruit. Bark rough, dark grey, wood grey often streaked, moderately hard, is used for planking-packing cases. The stem stick is also used as chewing stick in some places.

Pongamia glabra Vent (Fabaceae)

A moderate-sized nearly evergreen tree with 5 or more large ovate acuminate leaflets and pinkish-white flowers. Bark thick, grayish-brown, wood white and moderately hard. The stem stick is also used as a chewing stick. The seed oil is used for soap-making and also used in treatment of skin diseases and rheumatism. Leaves are used as manure and fruits are edible.

Salvadora Persica (Salvadoraceae)

The Miswak (miswak, siwak) is a natural toothbrush made from the twigs of the Salvadora persica tree (Arak). Miswak was used by the Babylonians some 7000 years ago; they were later used throughout the Greek and Roman empires and have been used by Jews, Egyptians and in the Islamic empires. It is believed that this precursor to the modern day toothbrush was used in Europe until about 300 years ago. Today, Miswak is being used in Africa, South America, Asia, the Middle East including Saudi Arabia, and throughout the Islamic countries. It has different names in different societies, for instance, miswaak, siwak, or arak are used in the Middle East; miswak in Tanzania; datun and miswak in India and Pakistan. The toothbrush tree, Salvadora persica is a small tree or shrub with a crooked trunk, seldom more than one foot in diameter, bark scabrous and cracked, whitish with pendulous extremities. The root bark of the tree is light brown and the inner surfaces are white, odour is like cress and taste is warm and pungent15,16,17. The use of the chewing stick is deeply rooted in many cultures. In the Middle East, the most common source of chewing sticks is the Arak (Salvadora persica) tree. Chemically, the air dried stem bark of S. persica through chemical studies showed that it is composed of trimethyl amine, salvadorine, chlorides, high amounts of fluoride and silica, sulphur, vitamin-C, small amounts of tannins, saponins, flavonoids and sterols. Its fibrous branches and roots have been used as toothbrushes.

It has been scientifically proved to be very useful in the prevention of tooth decay even when used without any other tooth cleaning means. The users of Miswak have shown a remarkable lack of tooth decay as compared to other chewing sticks.

Methods

Collection of chewing sticks

Samples of the most commonly used chewing sticks in India, namely Neem (Azadirachta indica), Babool (Accacia arabica), Banyan (Ficus bengalensis), Mango (Mangifera indica), Pongam (Pongamia glabra), and Miswak (Salvadora persica) (Fig. 1 and 2). Out of these six chewing sticks S. persica was obtained from the commercial source and other chewing sticks were collected from the respective trees grown in the campus of National College, Tiruchirappalli.

Preparation of extracts

Hundred gram of each of the chewing sticks were used in the experiment. The chewing sticks were cut into small pieces and ground to powder in a ball mill. The powder was kept separately in sterile, dry and screw-capped bottles, which were stored in a dry cool place before aqueous extraction. Each successive 10 gm quantity was put into a sterile screw-capped bottle to which 100 ml of sterile deionized distilled water was added. The extracts were allowed to soak for 48 hours at room temperature before the mixtures were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatants were used for antimicrobial activity.

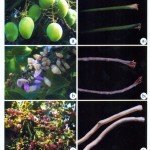

Isolation of Pathogens from Oral Cavity

The pathogens isolated from oral cavities from 25 students from the Department of Botany, National College, Tiruchirappalli revealed the presence of oral pathogens such as Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. lactis, Proteus vulgaris and Streptococcus mutans. From the heterogenous microbial colonies (Fig.2), pure colonies were isolated and grown in Nutrient Glucose Agar Medium18 for all the bacteria. Sabourand Dextrose Agar Medium19 was used for Candida albicans.

Antimicrobial Assay by Disc Diffusion Method

The prepared chewing stick extracts were tested for antimicrobial activity for oral pathogen by the disc diffusion method.20 The pure culture of the oral pathogens were individually streaked uniformly all over the Nutrient Glucose Agar and Sabourand Dextrose Agar media in 9 cm Petri dishes. The aqueous chewing stick extracts were loaded on plain sterile disc (Himedia SD 067) and placed on the medium in the Petri dish under sterile condition. Control discs with ethanol, methanol and standard antibiotic were placed as positive controls. The Petri plates were incubated at 37 ± 1° C for 48 hours. The experiment was carried out, in triplicate for each extract.

Results and Discussion

Antimicrobial effect of natural chewing stick extracts

The natural chewing stick extracts of six traditional Indian plants viz. Acacia arabica, Azadirachta indica, Ficus bengalensis, Mangifera indica, Pongamia glabra and Salvadora persica were selected and their antimicrobial susceptiblity test was conducted against six oral pathogens, viz., Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. lactis, Proteus vulgaris and Streptococcus mutans which cause dental caries, gingivitis and plaque. The results are tabulated (Table-1).

Table 1: Antimicrobial Effect of Chewing Stick against Oral Pathogen

| Pathogen | C | C1 | C2 | Aa | Ai | Fb | Mi | Pg | Sp |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0 | 0 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Candida albicans | 9.0 | 10.0 | 0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | 0 | 0 | 13.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 13.0 |

| Lactobacillus lactis | 0 | 0 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 13.0 |

| Proteus vulgaris | 9.0 | 10.0 | 0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 11.0 |

| Streptococcus mutans | 0 | 0 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.0 |

C : Ethanol

C1 : Methanol

C2 : Antibiotic disc (Cefepime [CPM] 30 mcg)

Aa : Acacia arabica

Ai : Azadirachta indica

Fb : Ficus bengalensis

Mi : Mangifera indica

Pg : Pongamia glabra

Sp : Salvadora persica

Antimicrobial effect of chewing sticks against oral pathogens

The chewing stick extract of Salvadora persica has shown the maximum inhibition zone of 13.0 mm for B. subtilis followed by Azadirachta indica 12.0 mm, Accacia arabica and Ficus bengalensis 10.0 mm while Mangifera indica and Pongamia glabra 8.0 mm respectively. The positive control antibiotic disc Cefepime 30 mcg have shown 13.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica (Fig. 3a and a1)

|

Figure 3

|

Salvadora persica chewing stick extract has shown the maximum zone of inhibition of 11.0 mm for C. albicans, followed by A. indica 10.0 mm, 9.0 mm for P. glabra, 8.0 mm for M. indica, 7.0 mm for both A. arabica and F. bengalensis. The positive control methanol have shown 10.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica and A. indica (Fig. 3b and b1).

The chewing stick S. persica has shown the maximum 13.0 mm zone of inhibition for L. acidophilus followed by 9.0 mm for A. arabica 8.0 mm for A. indica, 7.0 mm for F. bengalensis, M. indica and P. glabra. The positive control antibiotic disc Cefepime 30 mcg have shown 13.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica (Fig. 3c and c1).

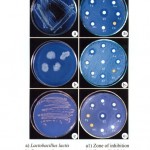

persica chewing stick extract has shown the maximum zone of inhibition 13.0 mm for L. lactis followed by 11.0 mm by A. arabica and A. indica whereas 9.0 mm by F. bengalensis, M. indica and P. glabra. The positive control antibiotic disc Cefepime 30 mcg have shown 13.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica (Fig. 4a and a1).

|

Figure 4

|

The chewing stick extract of S. persica, has shown the maximum inhibition zone of 11.0 mm for P. vulgaris followed by 9.0 mm by A. arabica and A. indica, 8.0 mm by P. glabra and 7.0 mm by both F. bengalensis and M. indica. The positive control methanol have shown 10.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica (Fig. 4b and b1).

The chewing stick extract of S. persica, A. arabica, and A. indica have shown the maximum inhibition zone of 11.0 mm for S. mutans whereas F. bengalensis, M. indica and P. glabra extracts were ineffective. The positive control antibiotic disc Cefepime 30 mcg have shown 13.0 mm of inhibition zone comparable to the effect of S. persica as well as A. arabica and A. indica (Fig. 4c and c1).

The selection of chewing sticks in Asian countries was based on a number of factors. The use of chewing sticks is most common in Asian countries especially in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East region, further more chewing sticks are cheap, readily available in urban and rural areas of the countries. Their taste is agreeable and not unpleasant and reported to have anti-plaque and many other pharmacological properties21.

A recent survey in Asia showed that more than half of the rural population used chewing sticks as an oral hygiene tool22. So it was important to find out the antimicrobial properties of those chewing sticks as they are so commonly used in Asian countries. It is claimed that the mechanical plaque-removing properties of chewing sticks may be similar to that of a conventional toothbrush23,24.

Most studies on chewing sticks have been carried out, where more than 90% of the population uses different types of sticks from trees that grow there such as Fagara zanthoxyloides, Serindei werneckei, Azadirachta indica, Accacia arabia25,26. Certain chewing sticks including those derived from Salvadora persica, A. indica and Accacia arabica are active against several types of carcinogenic bacteria frequently found in the human oral cavity25. Results from the present study showed that S. persica, A. arabia and A. indica showed maximum antibacterial activity against all the six tested microbes viz., B. subtilis, C. albicans, L. acidophilus, L. lactis, P. vulgaris and S. mutans. This result is in accord with the previous studies of Akpata and Akinremisi (1997)25, Al-Bagich and Almas (1997)27 and Almas Albagieh and Akpata (1997)28. The use of the chewing stick conforms with the notion of Primary Health Care Approach (PHCA) and the well established associations with certain cultural and religious beliefs. The chewing sticks have been proven effective as an oral hygiene tool and its use should be promoted with scientific rational and proper method of its preparation and usage. The use of chewing sticks will be a great help in developing countries with financial constraints and limited oral health care facilities for their population.

Conclusion

From this study, it could be concluded that S. persica is an effective antimicrobial agent for oral pathogens when utilized clinically as an irritant in the endodentic treatment of teeth with necrotic pulps.

Acknowledgements

The author (MNA) wish to thank DST-FIST, Government of India, New Delhi for providing the infrastructure facilities to the Department of Botany, National College, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu. Author also expresses thanks toSri K Ragunathan, Secretary and Dr K Anbarasu, Principal, National College, Tiruchirappalli for their encouragement.

References

- Williams S and Williams K, Clinical practice of dental hygienist, 7th ed, Esther W Willikins, London, 1994.

- Nigam P and Srivastava A B, Betel chewing and dental decay, Fed Oper Dent, 1990, 1, 36-44.

- Marsh P D, Microbiological aspects of the chemical control of plaque and gingivitis, Journal of Dental Resistance, 1992, 71, 1431-1438.

- Sachipach P, Osterkwalder V and Guggenheim B, Human root caries microbiota in plaque covering sound carious and arrested carious root surfaces, Caries Res, 1995, 29, 382-395.

- Guillemot D, Antibiotic use in humans and bacterial resistance, Current Opinion in Microbiology, 1999, 2, 494-498.

- Austin D J, Kristinsson K G and Anderson R M, The relationship between the volume of antimicrobial consumption in human communities and the frequency of resistance, Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 1999, 96, 1152-1156.

- Kim H, Park S W, Park J M, Moon K H and Lee C K, Screening and isolation of antibiotic resistance inhibitors from herb material resistant inhibition of 21 Korean plants, Natural Product Science, 1995, 1, 50-54.

- Ahmad I, Zaiba Beg A Z and Mehmood Z, Antimicrobial potency of selected medicinal plants with special interest in activity against pathogenic fungi, Indian Vet Med Jour, 1999, 23, 299-306.

- Ahmad I and Beg A Z, Antimicrobial and phytochemical studies on 45 Indian Medicinal plants against multi-drug resistant human pathogens, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2001, 74, 113-123.

- Chitme H R, Chandra R and Kaushik S, Studies on anti-diarrheal activity of Calotropis gigantea R. Br in experimental animals. J Phar Pharmacent Sci, 2003, 7, 70-75.

- Kim H S, Do not put too much value on conventional medicines, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2005, 100, 37-39.

- WHO (World Health Organisation, Prevention of Diseases), Geneva, 1987.

- Wu C D, Darout I A and Skang N, Chewing Sticks: Timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing, J Periodont Res, 2001, 36, 275-284.

- William Charles Evans, Trease and Evans Pharmacognosy, 15th ed, W B Saunders, London, 2002.

- Bhandari M M, Flora of the Indian Desert, 1st ed. Dhrti Printers, New Delhi, 1990.

- Kirtikar and Basu, Indian Medicinal Plants, 2nd ed, Vol II, International Book Distributors, 1987.

- The Wealth of India, A dictionary of Indian Raw Material and Industrial Product, Vol IX, Publication and Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, 1995.

- Allen O N, Experiments in Soil Bacteriology. Burgess Publishing Co, Minneapolis, Minn, USA, 1953, pp 65-70.

- Cavangh F, Analytical Microbiology, Academic Press Inc., New York, 1963.

- Dulger B and Gonuz A, Antimicrobial activity of certain plants used in Turkish Traditional Medicine, Asian J Plant Sci, 2004, 3, 104-107.

- Lewis M E, Plants and Dental Health, J Prevent Dent, 1990, 6, 75-78.

- Asadi S G and Asadi Z G, 1997, Chewing sticks and the oral hygiene habits of the adult Pakistani Population, Int Dent J, 1997, 47, 275-278.

- Hardie J and Ahmed K, The Miswak as an aid in oral hygiene, J Phillip Dent Assoc, 1995, 47, 33-38.

- Hattab F N, Miswak: The Natural Tooth Brush, J Clin Dent, 1997, 8, 125-129.

- Akpata E S and Akinremisi E O, Antimicrobial activity of extract from some African Chewing Sticks. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Path, 1997, 44, 717-725.

- Rotimi V O and Mosadomi H A, The effect of crude extracts of some African chewing sticks on oral anaerobes, J Med Microbiol, 1987, 23, 55-60.

- Al-Bagich N H and Almas K, In vitro antibacterial effects of aqueous and alcohol extracts of Miswak (Chewing Sticks), Cairo Dent J, 1997, 73, 221-224.

- Almas K, Al-Bagieh N H and Akpata E S, In vitro antimicrobial effects of extracts of freshly cut and 1 month old Miswak (Chewing Stick), Biomedical Letters, 1997, 56, 145-149.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.